In 1965, the British spy writer Len Deighton, better known for classics like The Ipcress File and later espionage thrillers, published two cookbooks. His first, Action Cook Book, tried to rehabilitate the kitchen as a masculine space, encouraging bachelors to flex their culinary muscles. The second drew more directly on his love of French cuisine. Deighton’s first visit to France was in 1946, having never left Britain before, and he described the experience of arriving into the tumult of post-war Paris:

“I was conspicuous in my civvy clothes for everyone had some sort of uniform, and most of them were burdened with packs and helmets and kitbags and rifles. Even the air was different in France; it smelled of Gauloises and garlic, and of the ersatz acorn coffee that had become the national beverage.”[1]

Those post-war encounters shaped his second book Où est le garlic?

Published in 1965, Deighton’s recognised the growing influence of cookery writers like Elizabeth David, who published 5 “epoch-making cookbooks” which celebrated Mediterranean cuisine between 1950 and 1960.[2] When publishing French Country Cooking in 1951, David noted that:

“The restrictions of years of rationing have been the cause of some remarkably unattractive developments in the serving of food in restaurants…”[3]

As Britain moved into the 1950s things began to improve, though the Italian chef Otello Schipioni talked of how olive oil and garlic had to be introduced cautiously, as “the British knew them only as medicine and hated the idea of them.”[4] While these ingredients were available in Britain, they were largely imported, often only available in delis catering to specific expatriate communities, and not yet widely frequented by the ordinary British shopper. Yet, if we cast back further into the war itself, we can see moments where that British aversion had to be overcome in full Len Deighton style with espionage and action.

Free French on the Isle of Wight

The wartime lack of garlic on the Isle of Wight had apparently led to a crisis of morale amongst Free French sailors based at Marvin’s Yard in Cowes. Around 300 sailors were based there by 1942, many of them former members of the French navy serving overseas who had refused to support the Vichy armistice and wanted to rally to Free France. The Admiralty War Diary gives a sense of the British approach to French sailors on 1 July 1940:

“Any further arrivals who belong to French fighting forces and who are anxious to continue struggle under General de Gaulle should be sent to U.K. at first opportunity. […] These men, volunteering to help our cause, are to be given every encouragement and are to be informed before despatch to U.K. that they are welcomed as brothers and that it is because we think that it is in our country, in the first instance that they can render the best assistance, that they are coming to England.”[5]

For French naval forces, the choice to side with Britain was not always automatic, especially after the scuttling of the French fleet at Mers-el-Kebir caused a rift amongst naval relations only 2 days later.[6] Yet, as soon as the Free French Navy was constituted by Admiral Muselier in October 1940, French sailors had a clear means to resist the Germans in support of the Allied cause. IWM Oral History interviews with Pierre L’Hours and Marcel Olivier tell of their deployment across different wartime theatres before finding themselves in Cowes on the Isle of Wight, serving in the Free French Navy.

These were far from forgotten forces, however, but part of a crucial French contribution to the Allied cause. We can see the memorial traces of that contribution in the plaque on The Parade at Cowes, which reads:

“CLOSE TO THESE PREMISES

IN MARVIN’S YARD

WERE BASED FROM 1940 TO 1945

THE FREE FRENCH SUBMARINE CHASERS

UNDER THE COMMAND OF CAPTAIN

FIRST DESTROYER FLOTILLA.

THEY WERE IN THE FIGHTING LINE

IN THE CHANNEL

NOTABLY IN THE COWES BLITZ

BRUNEVAL AND DIEPPE RAIDS

LIBERATION OF FRANCE”[7]

As noted in the inscription, the “chasers” (chasseurs, or hunters in the original French) took part in the defence of Britain. Cowes was subjected to a Blitz in May 1942, and the improvised French base was absolutely destroyed. The Marvin’s Yard building was hit and burned (including the wooden yachts inside), while the Polish destroyer ORP Błyskawica provided barrage defence.[8] A new base for the French sailors was constructed afterwards, and sailors recounted with pleasure that they now had access to hot water for showers, and other such amenities. As well as lodging on their boats, French sailors billeted with local families, near Marvin’s Yard in Cowes.[9]

The regular work of the “chasers” in Cowes was escorting convoys and patrols in the Channel and the Solent.[10] They also played an active part in the Bruneval raid against a German radar station in February 1942, and the daring but ill-fated Dieppe raid in August 1942. Crucially, the “chasers” also participated in support for the Normandy landings in 1944. Perhaps the most famous name amongst their number was General de Gaulle’s son, Philippe de Gaulle, stationed there as a young sailor.[11]

Thanks to the efforts of members of the Free French Descendants Group, especially the sons of Pierre L’Hours, documents relating to the Free French in Cowes have been digitised and presented online. This excellent resource includes images of the ships, as well as profiles of some of the veterans by their descendants, contextualising their wartime service and helping to preserve the memory of these Free French sailors.

Garlic by Lysander

The sailors recount their time on the Isle of Wight fondly in IWM oral history interviews, and they clearly created a sufficiently good impression amongst locals that they tried to secure home comforts for the Frenchmen. Bulbs of garlic were apparently sourced as part of a clandestine pick-up flight, according to local stories on the Isle of Wight reported in the local press as well as The Times, Guardian, Daily Mail, and Daily Mirror. The initiative was attributed to Bill Spidy, the landlord of the Painters Arms, and head of the local gardening club on the Isle of Wight.[12]

“The story was pieced together by Isle of Wight garlic farmer Colin Boswell who talked to Liz Holland, an ex-WAAF at Tangmere. She noticed a whiff from the sacks and Colin said: ‘She still remembered it because they were not used to it, such a strange smell.’”[13]

Intriguingly, at least two of the Free French sailors profiled on the ‘Free French in Cowes’ website, Raymond Delannoy and Joseph Santini, were chefs, and the recollections presented give a sense of how greater culinary variety might have appealed. Joseph Santini’s daughter also recalled her father’s lifelong commitment to cooking and his training as a pastry-chef on the French Riviera before the war.

Delannoy, pictured in chef whites, ran the kitchen on ship, and the testimony presented by his daughter tells of his visits to Newport market to secure ingredients for the kitchen, including live animals. On the train back from Newport to Cowes, we are told:

“He and his friends let the piglets loose to run around in the carriage. A posh lady with a feather in her hat opened the carriage door to come in, looked at the pigs running round, looked at the men and said one word loudly “Frenchmen!” and closed the door and walked off.”[14]

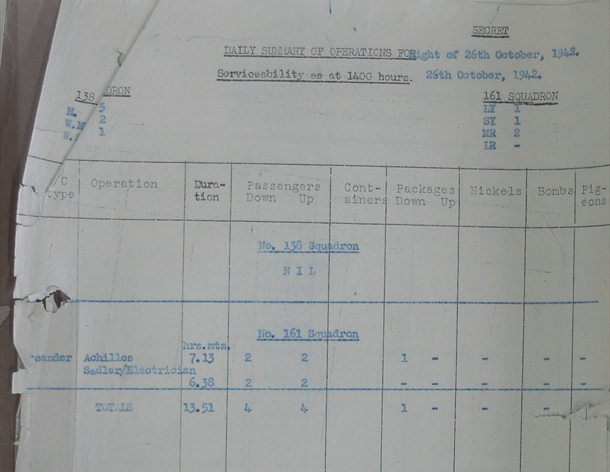

According to these reports, garlic bulbs were secured for the Free French naval personnel based at Cowes from one of the clandestine flights which took off from nearby RAF Tangmere in West Sussex, the forward operating base for 161 Squadrons, usually based at RAF Tempsford and available for clandestine flying from 1942:

“During the moon periods which enabled night flying (one week before and after the full moon), 161 Squadron’s Lysanders were run as a detached flight operating exclusively from RAF Tangmere in West Sussex.16 Pilots were based in Tangmere Cottage across the road from the main station, which provided a discreet entrance for arriving and departing under cover of darkness. The mantelpiece of that cottage held a sizeable collection of champagne bottles, trophies of the successful flights and tokens of gratitude from clandestine passengers.”[15]

On one of these flights, however, it was not champagne which was brought back from France, but – seemingly – garlic. Operation ACHILLES took off on the night of 26 October 1942, with a Westland Lysander flown by Fl Lt John Bridger leaving Tangmere for a landing ground east of Ussel in the Corrèze.[16] This landing zone was a relatively short lived one, as Hugh Verity relates:

“Twice in 1942 the little grass airfield at Thalamy, near Ussel, was used before the Germans obstructed it with stakes”[17]

The landing was made more difficult as the flare path which would normally guide the pilot in to land was dimmer than expected. This was because it had been laid out by the radio operator Arthur-Louis Gachet using “solid meta fuel” (firelighters for lighting a stove) rather than the normal flashlamps, as the intended operator Pierre Dallas had fallen asleep on the train on the way there, having been perpetually on the move for months beforehand “sleeping with one’s eyes open.”[18] Despite the flickering flare-path, Bridger brought the Lysander in to land and saw his passengers safely disgorged.

This was an important mission in intelligence terms, delivering two crucial passengers into France. The first was the “brilliant British wireless operator Ferdinand Rodriguez” working to support Marie Madeleine Fourcade’s Alliance network.[19] The next was working with MI9 to set up the Marie-Claire escape and evasion line, Mary Lindell. Having only escaped France in July 1942 (after serving time in prison throughout 1941), Lindell had been training in England, and her pilot Bridger reportedly told her how much he respected her daring to return to help others escape.[20] There was perhaps extra space to accommodate things in the Lysander for the return, as Fourcade’s brother Jacques missed take-off, running towards the landing strip after Bridger had already taken off on return to England.[21]

Many returning agents brought gifts and tokens from wartime France, as described by the Bertram family, whose home Bignor Manor served as a half-way house for agents being transported by Lysander. Alongside the already mentioned champagne at Tangmere Cottage, Barbara Bertram recalled:

“The number of presents they brought us was embarrassing. Innumerable books and bottles of wine and brandy for Tony, all marked Pour la Victoire, and all sorts of lovely things for me: scent, nylons, brooches, chocolates, flowers.” [22]

The radio operator Arthur-Louis Gachet who had hurriedly laid out the flight path at Thalamy had been to Bignor Manor as recently as February 1942 practicing wireless operations before he was dropped back into France at the end of April 1942.[23] While the pick-up flight was certainly not organised for culinary purposes, instead to support the Alliance resistance network and Marie-Claire escape line, it is certainly possible that the hurried reception committee on the ground at Thalamy may have given gifts of local foods in thanks (or perhaps in apology, given the challenges of the operation). While it does not seem possible to demonstrate conclusively that the garlic travelled back to England on this pick-up flight, the possibility is credible, and it is not impossible to see how the garlic might have made its way from Tangmere station to support nearby French servicemen.

Espionage Cooking

Today, the strongest legacies of this wartime Free French navy presence on the Isle of Wight are the memorials to the veterans and testimonies of their descendants. But one of the unexpected legacies is also perhaps the successful Garlic Farm on the island, which attributes the Solent Wight variety directly to Spidy’s wartime delivery from France.[24]

So, we have a pretty good idea of an answer to the question posed in Len Deighton’s second cook book, Où est le garlic? We know where it ended up and we also seem to have a pretty good idea of where it came from. The Garlic Farm has an excellent restaurant on site, which I’ve enjoyed visiting myself some years ago.

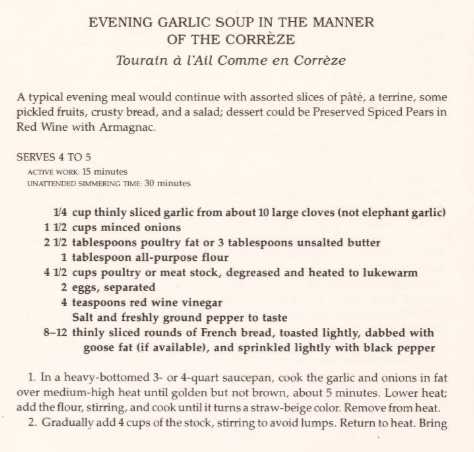

Unsurprisingly, the notional origin of the garlic – the Corrèze – does enjoy some renown for their local produce, with a recipe for a local garlic soup featured in this French cookbook.[25]

In the spirit of Deighton’s Action Cook Book, and in memory of the Franco-British cooperation which sustained wartime resistance against Nazi aggression, why not try making a pot of garlic soup this evening? And, sometime later, make plans pay a visit to the Isle of Wight’s Garlic Farm… perhaps by SD Lysander!

[1] Len Deighton, Len Deighton’s French Cooking for Men (London: Harper Collins, 2010), p.9.

[2] Christina Hardyment, Slice of life: the British way of eating since 1945 (London: BBC Books, 1995), pp.85-86, 91.

[3] Elizabeth David, French Country Cooking (London: Penguin, 2001), Batterie de cuisine.

[4] Christina Hardyment, Slice of life: the British way of eating since 1945 (London: BBC Books, 1995), p.90.

[5] Royal Naval War Diary, 01/07/1940, p.12. Accessed at [https://cd.royalnavy.mod.uk/-/media/rnweb/locations-and-operations/navy-historical-branch/pdfs/1940/war_diary_naval_1940_07.pdf] on 7/11/2025.

[6] ‘Interview with Marcel Jean Ollivier’, Imperial War Museum, 13/01/2000. Accessed at [https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/80018495?] on 6/11/2025.

[7] Memorials and Monuments on the Isle of Wight. Accessed at [http://www.isle-of-wight-memorials.org.uk/others/cowesfreefrench.htm] on 7/11/2025.

[8] ‘Interview with Marcel Jean Ollivier’, Imperial War Museum, 13/01/2000. Accessed at [https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/80018495?] on 6/11/2025.

[9] Julie Bishop, ‘Joseph Santini bio’, The Free French Navy in Cowes website. Accessed at [https://freefrenchnavycowes.webadorsite.com/santini-joseph] on 6/11/2025; ‘Interview with Marcel Jean Ollivier’, Imperial War Museum, 13/01/2000. Accessed at [https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/80018495?] on 6/11/2025.

[10] ‘Interview with Pierre Alexandre Maurice L’Hours’, Imperial War Museum, 13/01/2000. Accessed at [https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/80018490] on 6/11/2025.

[11] Bertrand Le Gendre, ‘L’amiral Philippe de Gaulle, fils du Général, est mort’, Le Monde, 13/03/2024. Accessed at [https://www.lemonde.fr/disparitions/article/2024/03/13/philippe-de-gaulle-fils-du-general-est-mort_6221725_3382.html] on 7/11/2025.

[12] ‘Isle of Garlic’, Wightwash, 2:83 (2020), pp.30-31 https://wightwash.org.uk/images/mag_archive/spring2020read.pdf

[13] Mark Branagan, ‘Secret WW2 mission saw garlic smuggled out from Nazi-occupied France for peckish French forces in Britain’, Daily Mirror, 30/07/2018. Accessed at [https://www.mirror.co.uk/news/uk-news/secret-ww2-mission-saw-garlic-13004751] on 6/11/2025.

[14] Christine Delannoy, ‘Raymond Delannoy bio’, The Free French Navy in Cowes website. Accessed at [https://freefrenchnavycowes.webadorsite.com/delannoy-raymond] on 6/11/2025.

[15] Andrew WM Smith, ‘Eclipse in the dark years: pick-up flights, routes of resistance and the Free French’, European Review of History: Revue Européenne d’histoire, 25:2 (2018), pp.392–414. https://doi.org/10.1080/13507486.2017.1411889

[16] Bertram, The Secret of Bignor Manor, p.289.

[17] Hugh Verity, ‘Some RAF Pick-ups for French Intelligence’, in KG Robertson (ed.), War, Resistance & Intelligence: Essays in Honour of MRD Foot (Barnsley: Leo Cooper, 1999), p.180.

[18] Hugh Verity, We Landed by Moonlight (Manchester: Crécy, 2005), p.53.

[19] Hugh Verity, We Landed by Moonlight (Manchester: Crécy, 2005), p.53.

[20] Peter Hore, Lindell’s List: Saving American and British women at Ravensbrück (Stroud: History Press, 2016), Chapter 9.

[21] Hugh Verity, We Landed by Moonlight (Manchester: Crécy, 2005), p.53.

[22] Bertram, The Secret of Bignor Manor, pp.196-197

[23] Bertram, The Secret of Bignor Manor, pp.69-70

[24] Dale Berning, ‘Garlic is an excuse to believe in magic’, The Guardian, 02/03/2013. Accessed at [https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2013/mar/02/garlic-excuse-to-believe-in-magic] on 7/11/2025.

[25] Pauline Wolfert, The Cooking of South West France (New York: Dial Press, 1983).